Relics of the Spanish and Mexican eras, the county’s oldest buildings have fascinating stories to tell.

Driving through busy modern-day Santa Cruz County, it’s hard to imagine a time when the rolling hills ran down to the sea uninterrupted by houses, bridges, roads and office buildings. But of course that’s what the first Spanish settlers found when they marched up from Monterey to establish a mission in 1791. To build the Misión de la Exaltacion de la Santa Cruz, they used the materials at hand—timber, felled at great effort and expense, and dirt, plentiful and free.

Given the two choices, it’s easy to see how adobe, a mixture of earth and water bound by straw or manure, became the predominant building material not just in Santa Cruz but throughout Alta California, as Spain worked to establish a foothold here. Santa Cruz County is home to four historic adobes from the Spanish and Mexican periods (1769-1850). Their stories track California’s own complex history of settlement by waves of soldiers, priests, and finally civilians, all with their own versions of the California dream.

The Mission Adobe at Santa Cruz Mission State Historic Park

The first European settlement in the area was the Santa Cruz Mission, built on the hill overlooking present-day downtown Santa Cruz. Established in 1791 by Spanish priests, it was the 12th of 21 missions meant to form the foundation of a Spanish-style society in California. The Ohlone-speaking indigenous people who lived at and near the mission labored in the fields and orchards, milled flour, and worked crafts and trades such as weaving, spinning, blacksmithing, and leather tanning.

Today Mission Hill is the home of California’s only surviving example of mission housing for indigenous people. A kind of early apartment house, the Mission Adobe is a long, low-slung structure one room wide and seven rooms long (the original building had 17 rooms), with walls two feet thick in the classic adobe style. Built between 1822 and 1824, its construction mirrored that of a dormitory that stood across the creek (where School Street now runs). These dwellings housed indigenous artisans and craftspeople and their families.

Now the centerpiece of Santa Cruz Mission State Historic Park, the Mission Adobe contains a wealth of information about Ohlone lifeways, as well as the history of the adobe as it passed from generation to generation, miraculously surviving earthquakes and real estate booms. It’s all that remains of the mission complex that once sprawled across this bluff overlooking Monterey Bay. Fun fact: The avocado tree that stands in the courtyard is thought to be the second oldest in California.

Santa Cruz Mission State Historic Park, 144 School St, Santa Cruz. (831) 425-5849. Check their website for updates.

The Branciforte Adobe

Not many people realize that Santa Cruz County is home to one of just three civilian settlements built by the Spanish. Unlike the missions and presidios with their religious and military functions, the pueblos were established as centrally planned farming communities with plazas and zoning—places where ordinary civilian life could eventually flourish. The first two pueblos were San Jose and Los Angeles. The third was Villa de Branciforte, established in 1797 across the San Lorenzo River from the six-year-old Mission Santa Cruz.

The Spanish authorities had grand plans for Villa de Branciforte, but it was hard persuading residents of established towns in New Spain (i.e., Mexico) to move to the wilderness. The first eight settlers who arrived by ship in Monterey from Guadalajara in May 1797 had been accused of petty crimes back in Guadalajara. Life in Branciforte, where they’d been promised housing, livestock and a stipend of $116 a year, was their ticket out of jail. Soon six young former soldiers joined them. One of them was Joaquin Castro, a son of a family on the first De Anza Expedition. The settlement kept growing and was eventually annexed to the city of Santa Cruz in 1905.

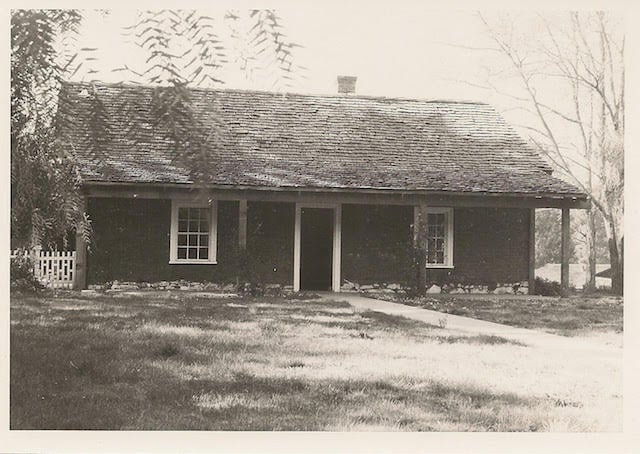

We don’t know much about who built the Branciforte Adobe or when it was built, but experts in adobe construction have suggested it was erected during the Spanish period (1797-1821) and continuously inhabited ever since. Maybe its first owners were fans of horseracing who wanted to be at the center of the action; the road that is now North Branciforte Avenue doubled as a racetrack back in Villa de Branciforte’s early days. Maybe the home was the scene of lively parties; one former resident who lived there in the 1870s claimed to have heard mysterious violin music emanating from the attic.

Today the Branciforte Adobe remains a private residence that stands at the southwest corner of North Branciforte and Goss streets in Santa Cruz, behind an adobe brick privacy wall. You can find the National Register plaque nearby on North Branciforte Avenue.

Private residence; please do not disturb occupants. North Branciforte and Goss streets, Santa Cruz.

The Bolcoff Adobe

One of the most colorful citizens of early Santa Cruz County was Jose Antonio Bolcoff, born Osip Volkov in Siberia in 1796. At the age of 19, Volkov deserted his Russian fur-trading ship when it anchored in the harbor at Monterey. In short order he had won himself a place in the town’s Spanish Californio society, working as an interpreter for the governor and taking a Spanish name. Seven years later Bolcoff married the well-connected Maria Candida Castro, the daughter of Joaquin Castro (the soldier who had settled in Villa de Branciforte), and the couple moved to Villa de Branciforte. By 1833 Bolcoff was the alcalde, or mayor, of the settlement.

The year 1839 was a big one for the Bolcoffs. Not only was Jose Bolcoff named administrator for Mission Santa Cruz—which had undergone secularization in 1834 and was being disassembled, piece by piece—but Maria Candida and her two younger sisters were given Rancho Refugio, a 12,000-acre land grant that includes what is now Wilder Ranch State Park. Jose and Maria Candida set up housekeeping at Rancho Refugio and built a home where the present-day parking lot is found. They also built the Bolcoff Adobe, believed to have been a farm building, using some of the beams and tiles from the Mission Santa Cruz.

By 1841, Jose Bolcoff’s name had mysteriously appeared on the Rancho Refugio grant, and the names of his wife‘s sisters had just as mysteriously disappeared. Decades later, in 1870, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the original grant had indeed been made to all three sisters and that Bolcoff had “suppressed or destroyed” the original and “fabricated” the new one. Read more about Wilder Ranch State Park.

Wilder Ranch State Park is located 15 minutes north of Downtown Santa Cruz on Highway 1, at 1401 Coast Road, Santa Cruz. Parking is $10.

The Rancho San Andrés Castro Adobe

Unlike most historic adobes in California, which are found in cities or towns, the Castro Adobe is in a rural area, gracefully situated on a hill overlooking the Pajaro Valley and Monterey Bay. The Adobe’s idyllic, relatively undeveloped location makes it easy for visitors to vividly imagine life there in 1849 when historians believe the two-story home was constructed by Juan Jose Castro, the son of Joaquin Castro and brother of the rightful owners of Rancho Refugio.

Castro family legend has it that the house was built with $30,000 from the gold fields. We may never know if that’s true, but unlike the Easterners and Midwesterners who had to first get to California before setting out for Gold Country, the Californios were able to race up to the Motherlode as soon as gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill and collect the easy pickings. In any event, once built, the Castro Adobe was a center of social activity, with feasts and entertainments, including bull-and-bear fights in the yard (it was a different time) and fandangos on the second floor.

After statehood in 1850, the Castro family was beset by lawsuits and eventually had to sell the family home. It passed through many hands, at one point being used as a barn. It was remodeled many times.

In the 1980s an adobe historian named Edna Kimbro bought the Castro Adobe, and, although the Loma Prieta Earthquake of 1989 almost destroyed it — and definitely rendered it uninhabitable — she worked tirelessly to have it purchased by the State of California to be repaired and turned into a state park emblematic of the Mexican Era in California. The State completed the purchase in 2002, and the Friends of Santa Cruz State Parks spearheaded a massive rehabilitation effort that began in 2009.

Today the Castro Adobe is the focal point of Rancho San Andres Castro Adobe State Historic Park. Fully restored and up to code, it features a wheelchair-accessible lift to the second floor, brand-new first- and second-floor verandas, extensive seismic retrofitting (which is not easy to do with historic earthen structures; the story will delight engineers types), and a functioning brasero, or traditional cooking range, that schoolchildren use for making tortillas on field trips to learn about the Californio era. Read more about the Castro Adobe.

Rancho San Andres Castro Adobe State Historic Park is on Old Adobe Road in Larkin Valley, near Watsonville. Visit their website for updates on operating status.

October 2020