The morning of January 6, 1926 dawned in Santa Cruz County like any other day of that heady time. Nationally, the stock market was picking up steam on its way to the wildest ride in history. Sears, Roebuck & Co. had just opened its first retail store, and booksellers were hawking a critically acclaimed new Jazz Age novel called The Great Gatsby. Down the coast in San Luis Obispo, the nation’s first “motorist’s hotel” had just opened its doors on the long shot that Americans would take to vacationing in their automobiles. And across the nation, the prohibition on alcohol was entering its seventh year.

That day, 22 federal agents swarmed nine locations in Santa Cruz County from the coast all the way up to Boulder Creek, seizing gin, whisky and the largest quantity of wine confiscated in the county since the start of Prohibition — some 36,000 gallons worth an estimated $100,000. If anyone was naïve enough to doubt that bootlegging, rum running and moonshining were alive and well in Santa Cruz County during those supposedly dry years, the big raid put those doubts to rest.

Rum Runners on The Bay

From the earliest days of Prohibition, the citizens of Santa Cruz County indicated that they were not universally interested in abstaining from alcohol. Though the National Prohibition Act didn’t officially take effect until 1920, Aptos declared itself dry in 1912 — and one colorful saloonkeeper wasn’t having any of it. Patrick Walsh, the 83-year-old proprietor of the Live Oak House in downtown Aptos (it stood roughly across Soquel Drive from the Bay View Hotel), ignored repeated orders to close down and eventually landed in jail in nearby Santa Cruz, where, local historian John Hibble tells us, he was allowed to serve out his sentence in an unlocked cell, playing cards and drinking whisky with his friends.

Once Prohibition became the law of the land, it wasn’t long before West Coast entrepreneurs with flexible mores began smuggling Scotch and whisky from Canada into the United States via California beaches. In time they developed a sophisticated system of transport that involved large ships sitting 12 or more miles off the coast (in international waters, beyond the reach of the Coast Guard) while powerful speedboats capable of easily outrunning the Coast Guard’s utilitarian vessels shuttled to and from the big boats with shipments of up to 500 cases at a time.

The remote, sandy shores of southern Santa Cruz County — in particular the string of beaches from New Brighton to La Selva, then known as Rob Roy — proved an excellent place to unload alcohol bound for San Francisco and the rest of Northern California. Here were friendly locals who would help unload the rum runners’ boats in exchange for a couple of bottles, cabins on neighboring ranches that could be used as stash houses, and law enforcement officials who could be paid to look the other way. Even the Cement Ship was used to store contraband.

To frustrated federal agents, it might have seemed like the whole town was in cahoots with the outlaws. Malio Stagnaro, the “Mayor of the Santa Cruz Wharf” until his death in 1985, recalled with amusement selling fuel to the rum runners on one side of the Santa Cruz Wharf and the Coast Guard on the other. According to his telling, the smugglers became downright brazen. While most liquor was delivered under cover of night, on one occasion they unloaded a shipment right onto the wharf in the middle of a Sunday afternoon, claiming it was salt.

Moonshiners and Monkeyshines

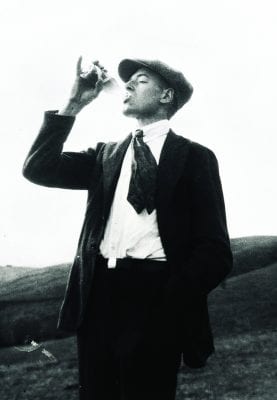

While the big-time rum runners did their thing, the small-time local moonshiners and bootleggers did theirs. Stills popped up all over the Santa Cruz Mountains to take advantage of good water sources and even better hiding places.

Paul Johnston, an Aptos businessman, property owner and mail carrier, remembered finding a 3-foot piece of copper coil lying in the middle of the road one day during his rounds. It turned out a Ben Lomond still had been warned of a bust and hastily relocated to Trout Gulch in the Aptos hills, losing a piece of equipment in the process. Johnston told a friend who had a brother in the Prohibition Service what he’d found, and the operation was stung not long after.

Moonshiners often used sugar to make nearly pure alcohol, selling it in 5-gallon cans to bootleggers who then added water along with burnt sugar for coloring or maybe some juniper berries for a fine bathtub gin effect. The resulting concoctions found their way into establishments all over the county: at the Garibaldi Villa Hotel on Front Street in Santa Cruz, next to the San Lorenzo River; at the Swiss Hotel on Water Street; at the lavish Hawaiian Gardens in Capitola, done up in the extravagant Orientalist style of the day with a lamplit waterfall and pool where guests could stash their bottles; and in countless other restaurants, hotels and dance halls that operated more or less in the open, paying the local constabulary for protection but resigned to the occasional bust by police “so it would look right,” as Stagnaro put it.

Days of Wine and Hijinks

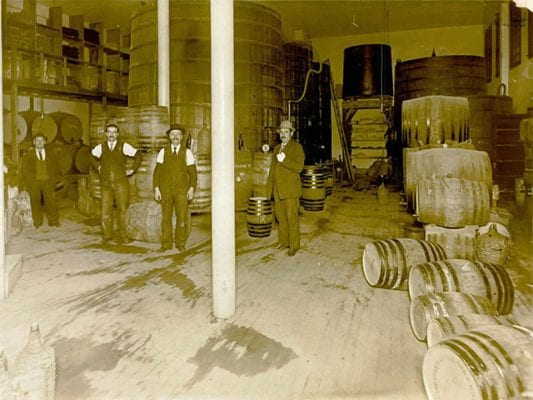

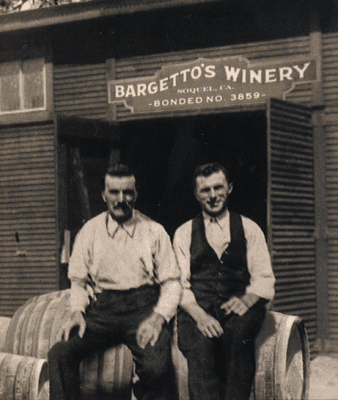

For the Italians of Santa Cruz County, Prohibition must have seemed crazy. They drank wine at every meal, gave it in diluted form to their kids, and generally considered wine drinking to be part of a civilized life. After Prohibition, families were allowed to make up to 200 gallons of wine — four barrels — a year for personal consumption. Some enterprising families decided to go above and beyond that. Among those were the Bargettos.

Filippo and Giovanni Bargetto had originally come from the Piedmont and worked as winemakers in the Bay Area until the looming threat of Prohibition forced a change of plans.By the mid-1920s, they and their wives Francesca and Ernestina, sisters from the Bargettos’ hometown in Italy, were farming fruits and vegetables in Soquel. Under financial pressure, and unable to help noticing a brisk trade in red wine all over Santa Cruz County, the brothers made their first batch of bootleg wine in 1926—six barrels. It sold in a trice. As Gianni’s grandson John E. Bargetto writes in the highly entertaining book The Great Prohibition Caper: Bootlegging in Soquel, the 1927 harvest of Zinfandel and Charbono grapes was irresistibly good, so the brothers decided to ramp up production that year to 22 barrels.

It was in the early months of 1928, as the young wine was slowly maturing in its oaken beds, that the Feds arrived. The scowling agents went away that day with a promise to return and what seemed like an end to the Bargettos’ dreams of winemaking. Things were looking grim until Johnny, as he now called himself, hit upon a scheme to save the wine. We won’t spoil the ending, so you’ll have to read the book for the whole story, but suffice it to say that with the help of a hand pump, friends with storage space and some ingenuity, the year’s production was saved. Today Bargetto Winery in Soquel proudly advertises the year of its establishment as 1933 — the year Prohibition ended. (So maybe they had a running start. Who’s counting?)

A Classic is Born

Prohibition eventually proved beneficial for the Bargettos, but it was an almost immediate boon for the Martinellis. A Swiss farmer’s son who had learned the art of making Champagne in France before coming to California in search of gold, Stefano Martinelli began making sodas—loganberry, sarsaparilla and ginger ale—in 1866 in his big brother’s shed in the Pajaro Valley. But he really hit the big time with the perfection of his Champagne-style apple cider, a beverage with 7.5% to 10% alcohol by volume. In 1890 Martinelli’s sparkling hard cider won the gold medal at the California State Fair. Its popularity soared, and soon Martinelli’s cider could be found all over California and in neighboring states.

Then, in 1915, Arizona — one of S. Martinelli & Co.’s biggest markets — banned alcohol. Suddenly the future wavered.

Martinelli’s son Stephen Jr., then studying at Berkeley, immediately started working with his professor on a pasteurization method to produce a shelf-stable fruit juice that could replace the alcoholic product. In the fall of 1917, Martinelli’s non-alcoholic sparkling apple juice reached the market. As the award-winning coffee table book S. Martinelli & Company: Celebrating 150 Years explains, uptake was slow at first, but once Prohibition hit, Martinelli’s became a festive and delicious stand-in for beer and wine, served in restaurants, elegant hotels and the fine dining cars of the Southern Pacific Railroad, and even featured in the movies. It became more popular during the Depression when Martinelli’s started marketing it in apple-shaped glass bottles, along with the popular “Drink Your Apple A Day” campaign.

By 1944 Martinelli’s was producing 600,000 gallons of sparkling non-alcoholic cider a year, 50 times the amount of hard cider it had been bottling before Prohibition. Today Martinelli’s remains the go-to non-alcoholic beverage for celebrating special occasions, on hand during holidays and at dinners with friends.

And it wouldn’t have happened without that odd 13-year experiment in forced abstinence.

Luckily Prohibition has ended. Visit Bargetto Winery, learn about Scenic Wineries in the Santa Cruz Mountains, read more about Martinelli’s 150th anniversary and find other entertaining stories from Santa Cruz County history.

Updated October 2020